500 miles. 24 hours. Infinite fish.

Shortnose Gar (Lepisosteus platostomus) with a Gizzard Shad (Dorosoma cepedianum). If you don’t like words, keep scrolling to find more photos and a video.

On a Mission

On the last day of the 2017 NANFA convention in Missouri, I drove several hours to fish some waters in the southeast corner of the state, led by Tyler Goodale, one of the fishiest people in MO. In the other car were a couple other NANFA members on a mission to capture (with dipnet and seine) some darter and sunfish species. My mission was to cast what Tyler suggested where he suggested.

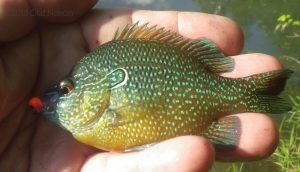

In the creeks and ponds Tyler guided us to, I managed to catch several species for the June Roughfish.com species contest and add three species to my lifelist: Redspotted Sunfish (Lepomis miniatus), Dollar Sunfish (L. marginatus), and Chain Pickerel (Esox niger).

The river I really wanted to fish, where Tyler knows every rock by heart and is on a first name basis with many of the fish and a few mink, and where he’s caught many species, including giant Longnose Gar and numerous Blue Suckers, was blown out, running too high and fast to even bother getting out of the car, so after some tasty pulled pork at a barbecue joint in the woods I headed back toward Illinois.

Warning: Systems Failure Imminent

I didn’t cross the Mississippi until after 10. Exhausted from a day in the sun and having driven at least 300 miles in the last 12 hours, with a couple hundred to go, I didn’t pay attention to my gas tank. In the middle of southern Illinois nowhere, AC blasting, music cranked up to keep me more or less awake, I (luckily) noticed the low gas warning light. I think maybe sunglasses or something were blocking it, but it’s possible I was just so out of it that even a bright orange glow in an otherwise orange-free darkness failed to register.

Exits were almost as few and far between as they’d been the time I nearly ran out of diesel fuel while driving a big truck across eastern Montana (it was fatigue that made me stupid that time, too, and I ended up having to buy 5 gallons from a farmer when the only station in range sold only gas). In northeastern Illinois, even when you’re out in the country, it is never far to a town. On this stretch of Interstate 57, there were, other than the road itself, few signs of human civilization—no town lights, no gas station signs or fast food beacons.

Some number of tense miles later, with the AC off to conserve a little fuel, when I did finally reach an exit with a gas symbol on the sign, I knew I was dangerously low. Exited. Crossed under the highway. Saw the station. Was halfway up the steeply inclined driveway to the pumps when the car sputtered and died. A few more yards was all I needed. The station itself had closed four minutes earlier, but the pumps were still on. I had no gas can, but I had a knife and a pop can, so I bought gas in 1 cup increments (charging each 37-cent cup separately) and poured it through an improvised funnel into my tank. It took about 10 to get enough in the tank for the car to start. At one point a state trooper pulled in to gas up. He didn’t have a gas can either, but offered to push my car from behind with his cruiser. I declined.

After that, my memory is hazy. I somehow managed to stay awake for 2 more hours until I reached a dam on the Big Muddy River. It had been one of those 20 hours awake, 12 hours of fishing, 500 miles of driving kind of days. I was completely exhausted when—around 1, I think—I arrived at the parking lot by the dam, but the combination of bright streetlights, occasional cars creeping slowly by, and residual adrenaline and caffeine meant that I dozed, off and on, for maybe four hours total.

Targets in Range

I woke at sunrise to birds singing and walked to the edge of the parking lot to see the boiling whitewater below the dam erupting with airborne Silver Carp. A few people were fishing. I’d fished here once before (in 2014), and found it difficult to avoid snagging Asian carp below the dam.

Silver Carp (Hypophthalmichthys molitrix) taking flight below a dam on the Big Muddy River in southern Illinois. June 2014. I was not able to catch any on hook and line, but I did snag two or three (though I never saw them and they might have been Bighead Carp). At least I caught this one in the air.

The view below the dam in 2014, with a heron minding my gear. The parking lot where I slept in 2017 is behind the streetlight visible in the upper left.

Engage

Not wanting to deal with Asian carp or other people, I drove to a secluded parking lot downstream and walked to the river to see if any gar were present. What I saw was mindblowing: hundreds of gar in a shore-to-shore feeding frenzy. Spotted and Shortnose gar shot past the rocks I stood on, hunting in 6 inches of water. All the way across the river, upstream and down, there were gar (also including Longnose) visible, many breaking the surface. A surprising number of them completely left the water, usually with a bill full of breakfast. It was literally impossible to look at the river and not see gar: flying gar, gar backs and fins, gar snouts, and gar splashes. (Unfortunately, there were also many dead gar in the rocks and floating, many with obvious arrow wounds. There were a lot of flies and, later, crows.)

Schools of Gizzard Shad passed me as well, pursued—often successfully—by gar. It was not a good day to be a shad, but it was going to be a great day to be me.

Three of the many gar hunting right up to the shore (and one that was killed and discarded by humans). Note the double-bubble burp right before it takes off. (If this isn’t animated, click on it.)

I jogged up the hill to the car, grabbed my gar rod and a box of lures, and returned to the water. My best guess is that I was rigged up and catching fish by 6:30 and that I was too tired and shredded to fish any longer by 8. I landed at least 2 dozen Shortnose and half a dozen Spotted gar (and lost dozens more), plus one very unfriendly Bowfin and a few Largemouth Bass. I hooked or (since there was no part of the water without a gar in it) snagged a gar on nearly every cast. Both spinners and crankbaits were hit the instant they entered the water, unless they landed on a fish and snagged it.

A few of the Shortnoses would probably have been new state records, but out of concern for the delicate feelings of the current record holder (let’s call him “Garman”) and because I was having too much fun, I let them all go.

The fishing action was so relentlessly intense that I only took a couple of photos, and this was my only shot of a Spotted Gar.

In addition to scratches and punctures inflicted by gars’ teeth and scales, with all the hook-setting and fighting the reel foot had raised and torn open a blister on the web between the middle and ring fingers of my rod hand and the reel’s handle had rubbed the skin raw on the index finger of my other hand.

At one point a very large gar threw the spinner, which flew directly at me. Two of the treble hook’s points pierced my shirt and skin. It didn’t get to the barbs, but did draw blood. It looked like a snakebite (or the mark of a vampire with a weak grasp on anatomy).

Sweaty, tired, sore, slimy, bloody, and fully satisfied before 8 in the morning: the Big Muddy had given me all the excitement of a really good day’s gar fishing, compressed into a little over an hour.

Observe

I returned to the car, guzzled all the water I had, swapped fishing gear for camera gear, and spent an hour trying to get photos of fully airborne gar. I ended up with hundreds of photos of splashes where gar had been milliseconds earlier, but also managed a few keepers. I used the GoPro for underwater video, but the water was very dirty and the results are not as impressive as I’d imagined. Still pretty cool, though.

(Click on any photo to get larger versions.) (Keep scrolling for video.)

- Airborne Shortnose Gar with a Gizzard Shad in-flight meal..

- Flying Shortnose Gar with an unlucky Gizzard Shad.

- Shortnose Gar with breakfast. I did what I could to bring a little clarity to a shot that was, unfortunately, out of focus.

- Shortnose Gar with Gizzard Shad. This photo was taken at a great distance, and this image is massively cropped.

- Gar fins were visible above the water all around me. It’s impossible to identify which species of gar this is.

- Shortnose (or Spotted) Gar hydroplaning.

- Shortnose (or Spotted) Gar with Gizzard Shad. Many of my photos showed only the splashes of gar landings.

- Gar scales at the surface

- Note the long form above the water in the background: a fully airborne gar with a shining shad in its mouth.

- Gar with Gizzard shad (detail from previous photo).

- Distant airborne gar. Note the shining shad at the top and the orange of gar fins near the water. (Detail from previous photo.)

- Bow wave of a gar.

- The eye of a captured Gizzard Shad is visible through the water. The gar’s eye seems to also be visible further to the right.

- I think the clearly visible eye belongs to a Gizzard Shad held in the jaws of a gar, and that the gar’s eye is visible further to the right.

- A gar greeting the day. This photo is cropped to an absurd degree, as this fish was quite far from my position. I like it anyway.

Speculate

In the 8 or so years I’ve pursued them, I have seen large populations of gar feeding aggressively many times, I’ve watched them launch from the water while trying to throw a hook or rope lure, and I’ve seen innumerable gar surfacing and splashing while breathing or attacking prey or lures, but I had never seen a gar launch itself completely out of the water with prey in its mouth, like a miniature Great White Shark flying into the air with jaws full of harbor seal. My photos of this behavior all seem to show Shortnoses doing it. I don’t know if the Spotteds and/or Longnoses were doing it as well.

So far, none of the gar-people I’ve shared the photos with have seen this behavior either. If I were a gentleman-scientist in the 1800s, I’d write a half page notice titled “Observation of a Potentially New Behavior in Garpikes in Illinois” and have no problem getting it published in a reputable journal.

Please comment if you’ve got info or have witnessed this.

As to why they were flying, I don’t know for certain. I have a few ideas that make sense to me but may have no foundation in reality.

This location, the downstream end of a narrow stretch of rapids 100-200 yards below the dam, is unlike any other spot nearby. The volume of water moving through this chute is high, and the amount of dissolved oxygen must be close to the maximum possible. Closer to the dam there are lots of airborne Silver Carp, along with less flight-prone Bighead Carp, but I observed none of them here. Below these rapids the river more than doubles in width and the water calms. The majority of the flying gar action was in the zone where the river transitions from rapids to flat water, and from narrow to wide. As can be seen in the photos and video, it is a chaotic mass of eddies, with currents flowing in all directions. I imagine the change in flow (speed, direction, volume) concentrates prey, though I’d want to know more about how Gizzard Shad handle and react to fast or swirling currents before taking this idea very far. If at least partly accurate, this would explain the sheer numbers of both gars and shad at this spot.

More interesting than their presence is their completely leaving the water in the act of grabbing prey. Though many were active at and on the surface there, few (if any) gar fully left the water in the rapids or the eddies directly below them. All of the full-aerial action was a little further downstream, where the water appears to be calmer and slower. Visibility underwater was very low (the underwater footage was shot with a camera about a foot below the surface), so one of my guesses is that it was easier for the gar to spot shad above them, either clearly or as silhouettes, and to aim upward at them. The turbidity of the water, and the fact that shad don’t sit still much, would make it difficult to use the usual float-up-slowly-like-innocent-driftwood-and-strike-suddenly approach. Maybe the gar, coming from below, could not judge the distance to their targets against the very bright sunlight hitting the murky water, and overestimated necessary intercept speed to the point that they left the water completely. Maybe they were just excited by the arrival of another lovely day.

How analogous is a gar’s vision to a GoPro’s? No idea. But if the physics of light in dirty water applies to gar eyes in a similar way, they would not have been able to see prey more than a couple feet away. I wonder how accurate a guide their lateral line is in chaotic flow, and how well it allows them to distinguish a shad from other feeding gar without visual info.

How dirty was the water? This dirty. Any passing gar (or shad) more than a foot or two from the camera was at best a shadow. (There’s lots more of this in the video.)

The low angle of the early morning sun hitting the suspended matter in the water may have made visual targeting still more difficult. I think the number of air-gar decreased as time passed and the sun got higher. At the time I didn’t think about this, assuming the shad were changing their behavior or moving deeper or to other areas, or even that the gar were getting full, but perhaps it got easier to hunt as the light changed.

Retreat

After all the slime, sweat and blood, even more exhausted, I drove another 6 hours and made it home in time for dinner.

According to my odometer, I drove over 1300 miles in 4 days.

I can’t wait to return, better prepared. I would like to try wading out into the frenzy—depth permitting—or anchoring in the midst of it in a kayak. Snorkeling through the action would be fun, but with bowfishers shooting gar…

Transmit

Finally, the video: (https://youtu.be/ZiLlAAeEQXw)

(I let the camera run for about half an hour underwater. The best few minutes are included in the video.)

Bonus: This water snake swam right over numerous gars (they’re there, but hard to see in the video I shot or this GIF). I watched it until it was out of sight, and was surprised that none of them grabbed it. I wonder if gar ever eat snakes. If not, why not?

Never seen anything like that before. Awesome pics and awesome video. Did you stumble onto a rare moment or do you think this happens often at this spot?

Thanks, Garmaster. I hope it’s a common occurrence there because I want to encounter it again with a more functional brain and better preparation.

Perhaps the jumping gar already caught their shad a few seconds earlier and are jumping to avoid another gar trying to steal it? Did you see any evidence of them trying to grab prey from another gar?

It had not occurred to me that the jumps could be separate from the capture of the shad. Thanks for that. I did consider the possibility that competition of some sort was involved. It could be that the sheer number of gars present made speed an advantage, and that momentum carried them out of the water. Avoiding theft is definitely a possibility. We have seen them swimming on the surface with beak and prey held out of the water (it looks like they’re showing off their catch), and I’ve wondered if that might be a way of keeping a freshly caught meal out of the sight of other gars until it’s positioned correctly for swallowing, or at least until there’s no question that the grip is good. Perhaps there is a window after catching a shad when it is most likely to be able to flop free, becoming an easy meal for an adjacent gar. I didn’t see any competitive behaviors or attempts at theft, but that would have happened below the surface. Snorkeling or deploying more underwater cameras further from shore might show some cool stuff.

I’ve never seen longnose gar jumping anywhere in Eastern Ontario, except when on the hook. I’ll keep an eye out this summer.

Love the essay, pics, AND videos!!

Go Gar!!!

Thanks!

Go gar!

I saw a big gar expend a large and completely unnecessary amount of energy hitting a completely dead and floating gizzard shad. the entire gar went airborne from the force of the hit on the dead shad.

This occurred in a wellhead canal off of Big Pigeon Bayou in the Atchafalaya Spillway. Water was pretty dingy and had no flow. That’s probably the only time I have seen a gar go airborne on a hit though.

Bro, this is awesome! I have watched hundreds of Spotted Gar feed in inches of wayer at night….hammering Shiners and Silversides. Nothing like this though….ao cool!

I seen what looked like a spotted gar grab a bird flying low at edge of the pearl River Columbia ms round daylight

Pingback: 14 Reasons Why Gar Fish Is Not Meant For Your Home Tank