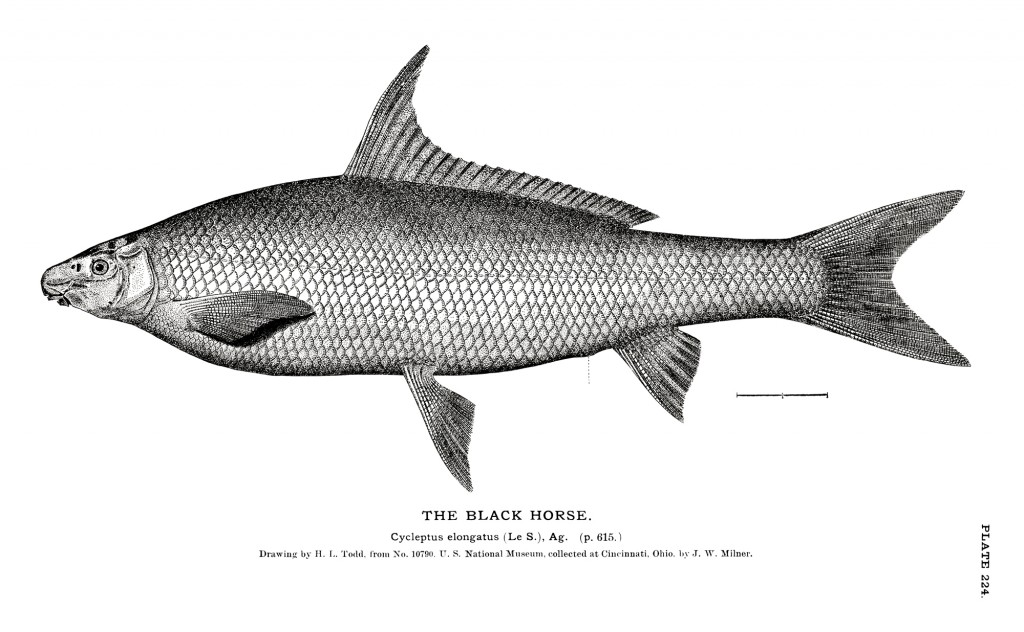

The Black Horse. H. L. Todd’s 1884 Cycleptus illustration based on specimen 10790 in the U. S. National Museum (Smithsonian). I was unable to locate the specimen in an online search of the collection, so it may have been renumbered or lost. (Plate 224 in The Fisheries and Fishery Industries of the United States, Section 1: Plates.)

The following was first published, in an abridged form, in American Currents, (http://www.nanfa.org/ac.shtml and see my post about AC and NANFA here) Vol. 40, no. 1 (January, 2015). This online version will evolve as I find new information, new images, and additional sources.

Fishing in the Public Domain

Unlike features such as scale or ray counts, the names of fishes—scientific and common—are susceptible to the same forces as any human creation. What initially seem like good ideas later fall from favor, new discoveries make old understandings obsolete, and the innovations of earlier generations are eventually old-fashioned. With this in mind, and believing them to be important, I keep track of every common or vernacular name I find for any sucker species. Old sources are especially rich in names, and I have examined hundreds of scientific, popular, and governmental publications (so far).

Thanks to the concept of public domain, 1 (click footnote numbers for information and downloads) the Internet Archive, the Biodiversity Heritage Library, Project Gutenberg, Google Books, and other online resources, it is possible to find obscure and very old sources. A staggering number of publications are freely available online, but much remains undigitized. Unpublished sources are a particular problem: rare or unique sources (field notes, unpublished manuscripts, correspondence, sketches) are easily lost, and those that survive are unlikely to be known, cataloged, or scanned. Any one of them might contain fragments of information (e.g., regional fish names and lore) that their authors never managed to fit into published works. Much remains hidden.

Until the 1930s, no serious attempt was made to standardize fish names, and even scientific names changed frequently. It can be difficult to know what species early observers of North American fishes meant, even when the names they used seem specific. Even the common names of trout and pike in old books are often confusing; the problem is magnified when dealing with less revered fishes such as suckers: suckers exist in almost all areas of the continent and have accumulated many regional and local names, they are frequently called carp, and sucker species were often treated—either out of ignorance of their differences or a feeling that these fish were unworthy of more careful attention—as the single species “suckers.”

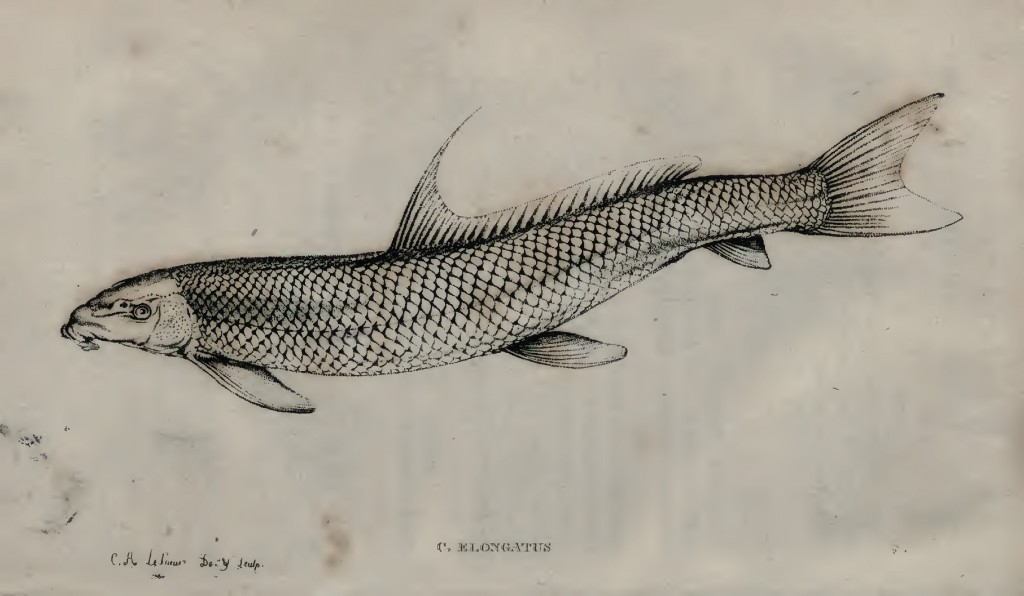

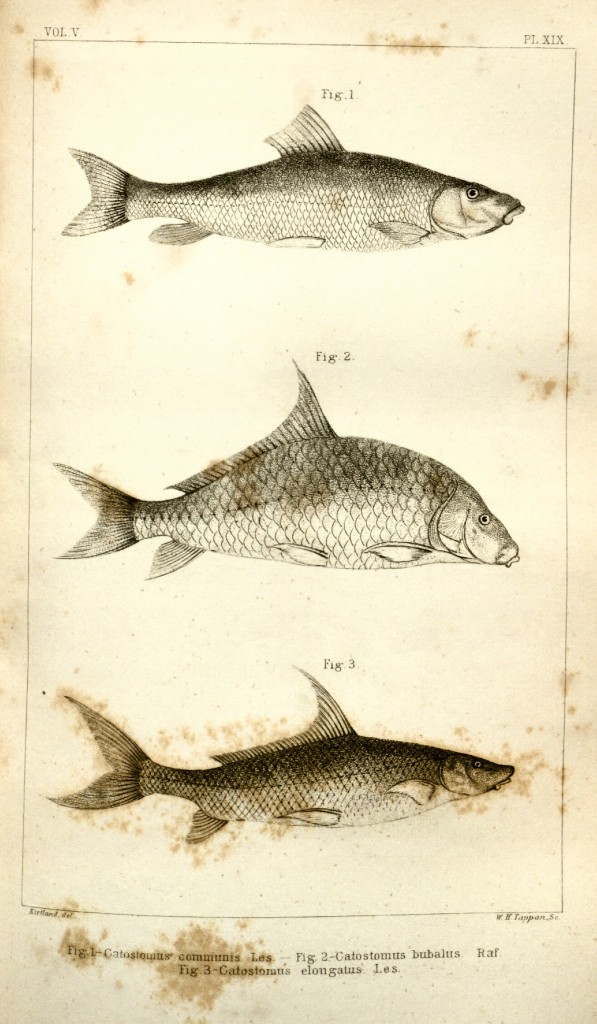

Figure 1. LeSueur’s illustration of a (dried) Blue Sucker, which he called Catostomus elongatus. [Plate between pages 102 and 103.] Kirtland (1845: 286) wrote, presumably in reference to this illustration, “Le Sueur drew his figure…from a dried specimen, and, with the exception of the dorsal fin, it has little or no resemblance to the recent fish.” Elsewhere (1838: 192), he wrote “C. elongatus. The Missouri sucker, and the black-horse and black-buffalo of the Cincinnati market. Lesuer’s [sic] figure of [it] has so little resemblance to this fish, that I drew a figure of it and prepared a description under the name of C. fusiformis, before I had any suspicions that we were both aiming at one species. The number of rays in the several fins and the form of the dorsal led me at length to arrive at this conclusion. He had seen only a dried skin.”

Cycleptus elongatus

The Blue Sucker was first described in 1817 by LeSueur as Catostomus elongatus (1817: 103-104). 2 Hot on his heels, Rafinesque (1820: 60-61) 3 described it twice: he gives LeSueur’s Catostomus elongatus as his 67th species (with the common names Long Sucker 4 and Brown Sucker), then adds a new genus, Cycleptus, which differs from Catostomus in having two dorsal fins. In this genus, as species 68, he puts Cycleptus nigrescens, with the common names Black Suckrel [sic] and Missouri Sucker. As usual, he was less than rigorous: he admits he has not seen this fish. I think we can assume that if he had, he would have noticed that it had just one dorsal.

As it is morphologically and otherwise unique, the Blue Sucker can not actually be in the genus Catostomus (or, indeed, in any other sucker genus). Since Rafinesque’s Cycleptus was the first genus other than Catostomus into which the species had been placed, it is the name Agassiz assigned the genus when he sorted it out in 1855. 5 However, LeSueur’s elongatus remained the proper species name, as it had priority over Rafinesque’s nigrescens.

Agassiz did leave open the possibility that if there turned out to be two species of Cycleptus, one would be nigrescens. Though there are now officially two species in the genus, with a third likely to be accepted, nigrescens has not been—and is unlikely to be—used. The Southeastern Blue Sucker (C. meridionalis), found in the Pearl and Mobile river basins of Mississippi and Alabama, was described by Burr and Mayden in 1999. Description of the Rio Grande Blue Sucker (known only as Cycleptus sp. until it has been formally described) is in progress. 6

As evidence of the importance of common names, Agassiz writes of Cycleptus (and of Rafinesque’s shortcomings): “the characteristics of the genus, as given by Rafinesque, are not true to nature. Yet…I do not feel at liberty to reject his generic name; since it is possible to identify the fish he meant by the vernacular name under which it is known in the West” (Agassiz 1855: 82-84). In other words, because Rafinesque had seen fit to write that “it is also found in the Missouri, whence it is sometimes called the Missouri Sucker” (Rafinesque 1820: 61), Agassiz could be certain that the species meant was the one still widely known by that common name.

Though its scientific name was sorted out in under 40 years—a quick resolution compared to some fishes—settling on a common name would take nearly three times as long, and priority would have no role at all in the decision.

Blue Sucker from Republican River, Kansas (April 2012). Photo by Paul Schumann. See http://www.roughfish.com/content/thousand-miles-blue-sucker for details.

Blue Sucker from Republican River, Kansas (April 2012). Photo by Paul Schumann. See http://www.roughfish.com/content/thousand-miles-blue-sucker for details.

Paul Schumann with a Blue Sucker from Republican River, Kansas (April 2012). Photo by Paul Schumann. See http://www.roughfish.com/content/thousand-miles-blue-sucker for details.

They really do get THAT blue! Blue Sucker from the Republican River, Kansas (April 2012). Photo by Paul Schumann.

Wisconsin River Blue Sucker (electrofished by Wisconsin DNR personnel, May 15, 2013). (Photo by Olaf Nelson)

Corey Geving, founder of roughfish.com, with a large Blue Sucker electrofished in Mississippi River Pool 2, Ramsey County, Minnesota, April 2007. (Photo by Jenny Kruckenberg)

Color Confusion

As names go, Blue Sucker is perfectly appropriate: these fish can be strikingly blue (see Paul Schumann’s photos, above). They may also be golden, pale gray (like the one Corey Geving is holding, above), jet black, brown, or combinations of these colors and more (like the Wisconsin River Blue Sucker, above). Interestingly, early descriptions of the species never mention the color blue. LeSueur states that he has only seen a dried specimen and can not comment on color. Rafinesque says Catostomus elongatus is “brownish” (and called Brown Sucker), while his Cycleptus nigrescens (which, remember, he had never seen) he describes as “blackish.” (Rafinesque 1820: 60-61) Kirtland (1845: 267) 7 comes closer to calling the Blue Sucker blue. Regarding color, he uses the word “glaucous” (meaning, according to several old dictionaries, powdery white, pale green, gray, or—in a few definitions—grayish blue) in his description of the head. A few lines below that, under the heading “Color,” he writes: “head dusky above, coppery on its sides. Back black, often slightly mottled. Sides and beneath dusky and cupreous. Fins dusky and livid.” Livid (again, according to a dictionary from the same period) could have meant black and blue, as a bruise. The entry in Jordan’s “Report on the Fishes of Ohio,” (1882: 814) 8 mentions color more than many: “the males in spring with a black pigment…coloration very dark, the females olivaceous and coppery, the males chiefly jet black with coppery shadings; fins dusky.”

For almost 100 years, no one specifically mentioned blue, the main color in most descriptions since the mid-1900s. Not until Forbes and Richardson’s The Fishes of Illinois (1908: 65-66) 9 does a description include blue by name (as opposed to “dusky,” “livid,” or “glaucous”): “color dark, bluish black about head; fins dusky to black; spring males almost black.”

The absence of blue may be explained by the loss of color in preserved specimens. Also, coloration can change over the course of the year, vary geographically, and respond to local water conditions. Blue suckers are sometimes light gray, for example, with virtually no color at all. Still, it is not possible that none of the biologists who wrote about it saw blue fish. Thus, “livid” probably indicates blue and black or gray, “glaucous” may mean grayish-blue, and “dusky,” a word most of the writers used (roughly as common a descriptor of color as black and coppery), might mean the gray-blue of a dark sky. “Coppery” or “cupreous” could have been intended to evoke the blue-green of oxidized copper, but I think it is more likely that it was intended to convey the metallic appearance of scales (like the Wisconsin River specimen above). As far as the dominance of black in descriptions—including many in which there is nothing that could possibly suggest blue—and in common names, it is worth noting that specimens were more easily collected in the spring (during the spawn). Since fish are often reported as being darkest at that time, those biologists who saw live or fresh fish would have been seeing them at their darkest. On the other hand, I have handled—and have seen many photos of—blue Blue Suckers during the spawn.

The Many Names of Cycleptus elongatus

Common names found in various publications, 1820 to 1950:

- Black Buffalo

- Blackhorse

- Black Sucker

- Black Suckerel

- Bluefish

- Brown Sucker

- Gourdmouth

- Gourdseed Sucker

- Gourd Sucker

- Long Sucker

- Long Buffalo

- Mississippi Sucker

- Missouri Sucker

- Muskellunge (Wabash River, IN, only)

- Razorback Sucker

- Schooner

- Slenderhead(ed) Sucker

- Shoemaker

- Shoenaher

- Suckerel

- Sweet Sucker

- Sweet Suckerel

When did the Blue Sucker turn Blue?

No one used Blue Sucker for C. elongatus until the 1920s, but the name itself was not new. Rafinesque (1820: 58) reports it as a “vulgar name” for his Black-back Sucker (Catostomus melanotus; generally believed to actually be Central Stoneroller, Campostoma anomalum). A list of Manitoba fishes received by The Smithsonian (Annual Report 1883: 231) 10 includes Catostomus teres (now C. commersoni, the White Sucker) as “Blue sucker” (oddly, another specimen of C. teres is identified as “Black Sucker” later in the same list). A “Large-scaled sucker, or blue sucker,” (no scientific name given) appears in The Market Assistant (DeVoe 1867: 296), 11 a book of food items available in the markets of East Coast cities, but it is too small to be Cycleptus. Goodholme’s Domestic Cyclopaedia of Practical Information has “blue sucker” twice: first under Chub, then under Sucker (described as small, pale-blue, and not worth eating) (1889: 105; 516). 12 As a final example of misdirection, Evermann, in The Bulletin of the United States Fish Commission (1896: 172), 13 gives Black Sucker and Blue Sucker as common names for Pantosteus jordani (now Catostomus platyrhynchus, the Mountain Sucker).

Meanwhile, the common names used for C. elongatus throughout the first century of its existence in the literature were remarkably consistent. Most texts that gave any at all used one or more of four main common names. Roughly tied for the lead were Blackhorse (as one word, two words, or hyphenated) and Missouri Sucker, with Gourdseed Sucker and Suckerel slightly behind but basically standard.

The origin of the first half of Blackhorse is obvious, and as with redhorse, the reference in the second half seems to be to the supposed resemblance of the heads of these fishes, in profile, to the head of a horse. (Encyclopedia Americana, 1920) 14 The logic behind Gourdseed Sucker is not (yet) clear to me. I have seen suggestions that it refers to the shape of the fish’s body, the shape or size of its mouth, the shape of its scales, or to the tubercles seen during spawning, which might have been seen as resembling gourdseed corn, an old variety common in the Ohio valley. 15 Missouri Sucker can be read as referring to the presence of the species in the Missouri River or to its existence in the Mississippi River and its tributaries in the state of Missouri 16 Though I have wondered about the origin of Suckerel for years, I have found only one explanation. According to the 1900 edition of The Century Dictionary, the name is the product of combining “sucker” with “-erel,” as in pickerel. 17 In the case of pickerel, “-erel” is the dimunitive suffix added to pike to mean “small pike,” but I doubt those who first used Suckerel knew this. It seems more likely that it came from the same sort of name-copying impulse that caused—and still causes—people to call everything from Largemouth Bass to Bowfin to Yellow Perch “trout.” For numerous examples of this, see Cloutman and Olmstead’s “Vernacular Names of Freshwater Fishes of the Southeastern United States.” 18

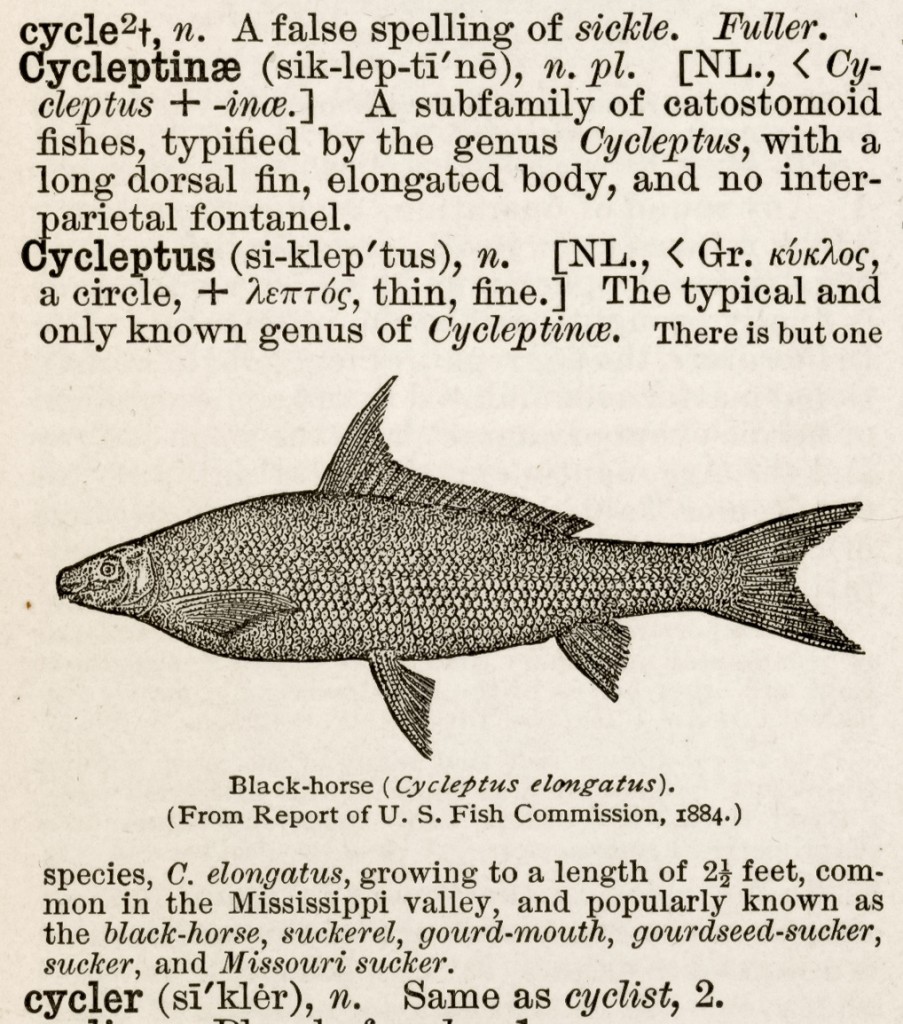

Cycleptus (Black-horse) from the Century Dictionary and Cyclopedia (1899). Note that the woodcut is a simplified version of H. L. Todd’s. Many illustrations of the species in the late-1800s use Todd’s image or variations on it.

The earliest appearance of Blue Sucker as a common name for Cycleptus elongatus that I have found is in two 1929 articles by Robert E. Coker on the fish and fisheries impacts of the Keokuk Dam. In the first (“Keokuk Dam and the fisheries of the upper Mississippi River”), he twice identifies the species as “Missouri or blue sucker” (1929a: 94, 100), 19 but after that uses only Blue Sucker. In the second (“Studies of common fishes of the Mississippi River at Keokuk”), he consistently uses only Blue Sucker, though he does give “bluefish” as an alternative common name, along with Missouri Sucker (1929b: 182). 20

Though Coker had clearly made his decision, the name did not spread quickly. While he worked at Keokuk (roughly from 1913–28), other publications continued to use the older names. The Encyclopedia Americana (1920) 21 has “Blackhorse, a fish, one of the suckers of the Mississippi Valley (Cycleptus elongatus); also known as the Missouri or gourdseed sucker. It is about two feet long, with a small head, suggesting, in profile, that of a horse, and becomes almost jet-black in spring.” Forbes and Richardson, in The Fishes of Illinois (1908, but unchanged in the 1920 edition), are inconsistent. Missouri Sucker is the common name used in the table of contents (p. v) and one table (p. cxix), but “Black-horse” is used in four other tables (pp. lxx, lxxx, lxxxix, and xcvii). They report later that “to Illinois and Mississippi River fishermen in this state it is commonly known as the Missouri sucker, or occasionally as the black sucker. The name ‘black-horse’ we have not found in current use” (p. 66). 22 Jordan and Evermann’s Check List of the Fishes (1896, but unchanged in the 1928 edition) provides four common names, none of which are Blue Sucker (p. 238). 23 Two works published in 1935 mention Cycleptus: Greene’s The Distribution of Wisconsin Fishes gives Blue Sucker as the species’ sole common name (p. 57), 24 while Pratt’s second edition of A Manual of Land and Fresh Water Vertebrate Animals of the United States gives only Blackhorse and Missouri Sucker, despite stating in the preface that the main purpose of the new edition is to provide updated names (p. 54). 25

Coker’s work may be the earliest publication of the name, but it seems unlikely that he coined it himself. In 1913 he sent a colleague to observe the closing of the gates of the newly completed Keokuk Dam to fill the lake above it. Locals harvested fish stranded in pools below the dam (over a ton), and the list Coker gives uses mostly vernacular names (e.g., “sheepshead, fiddlers”). Among the most numerous were “bluefish (Cycleptus)” (Coker 1913: 10). 26 In this context, “bluefish” seems to be a local name. As Coker repeatedly cites local informants for all sorts of information in all his articles, I suspect Blue Sucker, like “bluefish,” was a name he heard from fishermen, fish sellers and other locals. I hope his notebooks or other unpublished papers survive somewhere.

Blue Sucker appears more and more frequently in the 1930s and 1940s, though the old names persist. For example, both the 1943 (original) and 1947 (revised) editions of Eddy and Surber’s Northern Fishes use Blue Sucker but give the four traditional common names and call it “the blue, or Missouri, sucker” (1943: 108; 1947: 127). 27 Perhaps the authors, who must have known about the efforts of the American Fisheries Society to establish accepted common names, saw that Blue Sucker was the leading contender but understood it was not yet universally established. The 1974 edition of the book, of course, gives only Blue Sucker (pp. 279-80). 28

Making it Official

Though Blue Sucker had gradually gained traction for almost two decades, it did not become the “official” accepted common name until 1947. Compilation of “A List of Common and Scientific Names of the Better Known Fishes of the United States and Canada,” released in 1947 by the American Fisheries Society (and available by mail for 25 cents) had been underway since the 1930s. It was intended to help eliminate confusion caused by the “several groups applying [different] common names to fishes [including] sport fishermen; commercial fishermen; fishculturists; and scientific workers,” and “by purely local names applied to the same fish in different geographical areas” (p. 355). 29 Having worked to make sense of the evolution of common names for years, I applaud the effort.

The upstart name Blue Sucker was chosen over all of the species’ previous names (p. 361). The index at the end of the AFS list includes rejected names, but Missouri Sucker is the only one of the Blue Sucker’s former names included (p. 383). It seems unlikely that no other names were considered, given that the vast majority of published sources had consistenly also mentioned Blackhorse, Suckerel, and Gourdseed Sucker. Additionally, Missouri Sucker was not eligible for acceptance, since the naming committee’s rules explicitly disqualified geographic terms unless appropriate for a species with a restricted range.

The list’s introduction mentions disagreement and multiple rounds of voting (less than half the names on the list were unanimous choices), but not which fishes’ names were contentious. Though I would like to think Cycleptus was a hot topic, I have found no record of what—if any—discussion or debate was involved in the decision. I continue to hold out hope that notes exist in the papers of some committee members, but finding them will not be easy. The AFS is not aware of any records of the process, and Walter H. Chute, chairman of the committee, apparently left nothing in his papers archived at the Shedd Aquarium (he was its director at the time). If Reeve M. Bailey—a member of the first committee and its next chairman—left notes, they might be among his papers at the University of Michigan (and I intend to find out).

In the end, Blue Sucker was probably the right choice. It identifies the species’ family (suckers) and uses a modifier (blue) that is not applicable to other species of similar size or range. The fish is blue, of course, and the name Blue Sucker (whatever its origins) had been in use for at least two decades.

Still, I wish they had chosen Blackhorse.

(List of sources and footnotes below.)

Thanks to:

Alisun DeKock (Manager of Information Services and Archive at the Shedd) for looking in Walter Chute’s papers at the Shedd Aquarium; Aaron Lerner (AFS Director of Publications) for answering my questions about whether the AFS has any records from the Names Committee in the 30s or 40s; Carter Gilbert (Curator Emeritus of the Florida Museum of Natural History) for several useful suggestions; Christopher Scharpf (of http://www.etyfish.org) for commenting on my ideas and suggesting new areas of inquiry; and anyone else I consulted, bothered, or otherwise pulled into this project.

Sources

I only casually followed any systematic or accepted bibliographic format here, so please cut me some slack if you’re an editor (which I am, sometimes) or English teacher (which I was).

Agassiz, Louis. “Synopsis of the Ichthyological Fauna of the Pacific slope of North America, chiefly from the collections made by the U. S. Expl. Exped. under the command of Capt. C. Wilkes, with recent Additions and Comparisons with Eastern types.” The American Journal of Science and Arts. Vol. 19, no. 55. (May 1855) pp71-99.

Download PDF:

Agassiz 1855 (suckers only) (3321 downloads )

Read: http://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/ia/mobot31753002152467, http://www.archive.org/details/mobot31753002152467

“A List of Common and Scientific Names of the Better Known Fishes of the United States and Canada.” Transactions of the American Fisheries Society, vol. 75, no. 1. 1948, pp. 353-397.

Annual report of the Board of Regents of the Smithsonian Institution for the year 1883.

Read: https://archive.org/details/annualreportofbo1883smit

Bean, Tarleton H. The Fishes of Pennsylvania, With descriptions of the Species and Notes on their Common Names, Distribution, Habits, Reproduction, Rate of Growth and Mode of Capture. In: The Report of the State Commissioners of Fisheries for the years 1889-1891. Harrisburg, 1891, pp. 24-25.

Download PDF:

Bean Fishes of Pennsylvania 1891 (2852 downloads )

Read: https://archive.org/details/reportofstatecom1889penn.

Becker, George C. Fishes of Wisconsin. University of Wisconsin Press, 1983.

Full text online: http://digital.library.wisc.edu/1711.dl/EcoNatRes.FishesWI

Bessert, M. L. 2006. Molecular systematics and population structure in the North American endemic fish genus Cycleptus (Teleostei: Catostomidae). Unpublished Ph.D. dissertation, University of Nebraska. PDF: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1000&context=bioscidiss

“Blackhorse.” Encyclopedia Americana. 1904 vol. 3.

https://books.google.com/books?id=xmdMAAAAMAAJ (straight to page:

https://books.google.com/books?id=xmdMAAAAMAAJ&vq=cycleptus&pg=PT8#v=snippet&q=cycleptus&f=false)

“Blackhorse.” Encyclopedia Americana, 1920 (online): http://en.wikisource.org/wiki/The_Encyclopedia_Americana_%281920%29/Blackhorse

Buffler, Rob, and Tom Dickson, Fishing for Buffalo: A Guide to the Pursuit and Cuisine of Carp, Suckers, Eelpout, Gar, and Other Rough Fish (2009, U. of Minnesota Press).

Burr, B. M., and R. L. Mayden. 1999. “A new species of Cycleptus (Cypriniformes: Catostomidae) from Gulf Slope drainages of Alabama, Mississippi, and Louisiana, with a review of the distribution, biology, and conservation status of the genus.” Bulletin of the Alabama Museum of Natural History 20:19-57.

(The entire issue is free to download from the publisher at https://almnh.museums.ua.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2018/12/BALMNH_No_20_1999.pdf)

Buth, D. G., and R. L. Mayden. 2001. “Allozymic and isozymic evidence for polytypy in the North American catostomid genus Cycleptus.” Copeia 2001:899-906.

Cloutman, Donald G., and Larry L. Olmstead. “Vernacular Names of Freshwater Fishes of the Southeastern United States.” Fisheries, Vol. 8, No. 2: March-April, 1983.

(It is sad that this article did not spawn a raft of similar efforts across the U.S.)

Coker, Robert E. “Keokuk Dam and the fisheries of the upper Mississippi River.” Bulletin of the U. S. Bureau of Fisheries. Vol. 45. 1929. pp87-139.

Read/download: http://fishbull.noaa.gov/45-1/coker.pdf

Coker, Robert E. “Studies of common fishes of the Mississippi River at Keokuk.” Bulletin of the U. S. Bureau of Fisheries. Vol. 45. 1929. pp. 141-225.

Read/download: http://fishbull.noaa.gov/45-1/coker1.pdf

Coker, Robert E. “Water-Power Development In Relation To Fishes And Mussels Of The Mississippi” (Appendix VIII to the Report of the U. S. Commissioner of Fisheries for 1913.)

Read: http://www.archive.org/details/annualreportofco1913uniteds, http://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/ia/annualreportofco1913uniteds

“Cycleptus.” The Century Dictionary and Cyclopedia, vol. II. (1899) p. 1422.

De Voe, Thomas F. The market assistant, containing a brief description of every article of human food sold in the public markets of the cities of New York, Boston, Philadelphia, and Brooklyn; including the various domestic and wild animals, poultry, game, fish, vegetables, fruits &c., &c. with many curious incidents and anecdotes. New York, 1867.

Eddy, Samuel, and Thaddeus Surber. Northern Fishes: With Special Reference to the Upper Mississippi Valley. University of Minnesota Press. Minneapolis, 1943.

Eddy, Samuel, and Thaddeus Surber. Northern Fishes: With Special Reference to the Upper Mississippi Valley. University of Minnesota Press. Minneapolis, 1947.

Read: https://archive.org/details/northernfisheswi00eddy, http://biodiversitylibrary.org/item/29018

Eddy, Samuel, James Campbell Underhill and Thaddeus Surber. Northern Fishes: With Special Reference to the Upper Mississippi Valley. U of Minnesota Press, 1974.

Evermann, Barton Warren. “A Report upon Salmon Investigations in the Headwaters of the Columbia River, in the State of Idaho, in 1895, Together with Notes Upon the Fishes Observed in that State in 1894 and 1895.” In Bulletin of the U.S. Fish Commission. 1896. pp. 151-202.

Read: http://fishbull.noaa.gov/16-1/161toc.html

Evermann, Barton Warren and Ulysses Orange Cox. “A Report upon the Fishes of the Missouri River Basin,” Appendix 5 from The Report of the U. S. Commissioner of Fish and Fisheries for 1894. (1896) pp. 325-429 p389.

Read: https://books.google.com/books?id=_kM9AAAAYAAJ

Forbes, Stephen Alfred and Robert Earl Richardson. The Fishes of Illinois. Danville: Natural History Survey of Illinois, State Laboratory of Natural History, 1908.

Download PDF:

Forbes Richardson Fishes of Illinois 1908 Suckers (2993 downloads )

Read: http://biodiversitylibrary.org/bibliography/5033, https://archive.org/details/fishesofillinois1908aforb

Goode, George Brown. American Fishes: A Popular Treatise Upon the Game and Food Fishes of North America with Especial Reference to Habits and Methods of Capture (Boston. Estes and Lauriat, 1888).

Download PDF:

Goode 1888 Suckers (3258 downloads )

Read: http://www.archive.org/details/americanfishespo00good, http://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/ia/americanfishespo00good

Goode, George Brown. The Fisheries and Fishery Industries of the United States, Section 1: Plates. Washington, 1884.

Read: http://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/ia/fisheriesfisheryx01good, https://archive.org/details/fisheriesfisheryx01good, and finally (and most completely) http://celebrating200years.noaa.gov/rarebooks/fisheries/welcome.html (it’s in Section 1, Plates, part 2)

Goodholme’s Domestic Cyclopedia of Practical Information. New York. 1882.

http://archive.org/details/goodholmesdomest00good

Greene, Carroll Willard. The distribution of Wisconsin fishes. State of Wisconsin Conservation Commission. Madison, 1935.

Harlan, James R., and Everett B. Speaker. Iowa Fish and Fishing. Iowa State Conservation Commission, 1951, 1969 (and 1956?).

Hobbs, Orlando. “A List of Ohio River Fishes Sold in the Markets.” In Bulletin of U.S. Bureau of Fisheries, Vol 1. Washington, 1881, pp. 125-26.

Download PDF:

Hobbs Ohio River Fishes 1881 (3762 downloads )

Read: http://biodiversitylibrary.org/item/22550

Hubbs, C., R. J. Edwards and G. P. Garrett. 2008. “An annotated checklist of the freshwater fishes of Texas, with keys to identification of species.” Texas Academy of Science. Available from: http://www.texasacademyofscience.org/ Permanent link: http://hdl.handle.net/2152/6290

Jordan, David Starr. “Report on the Fishes of Ohio,” in: Report of the Geological Survey of Ohio, Vol. IV: Zoology and Botany, Part I: Zoology, Section IV. Columbus. 1882. pp. 735-1002.

Jordan, David Starr, and Charles H. Gilbert. Synopsis of the fishes of North America. In Bulletin of the United States National museum. no. 16. Washington, 1882.

Download PDF:

Jordan Gilbert Synopsis 1882 Suckers (2946 downloads )

Read: https://archive.org/details/synopsisoffishes00jord, http://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/ia/synopsisoffishes00jord

Jordan, David Starr and Barton Warren Evermann. A Check-list of the Fishes and Fish-like Vertebrates of North and Middle America. Washington. Government Printing Office. 1896.

Download PDF:

Jordan Evermann Check-List 1896 Suckers (2608 downloads )

Jordan, David Starr, and Barton Warren Evermann. American Food and Game Fishes. New York, 1908.

Download PDF:

Jordan Evermann American Food Game Fishes 1902 Suckers (2851 downloads )

Read: http://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/ia/americanfoodgame1902jord, https://archive.org/details/americanfoodgame1902jord

Kirtland, Jared P. “Descriptions of the Fishes of the Ohio River and Its Tributaries.” Boston Journal of Natural History. Vol. 5. no. 2 (1845), pp. 265-276, [and plates].

Download PDF:

Kirtland BJNH 1845 Suckers and plates (3228 downloads )

Read: http://biodiversitylibrary.org/item/100572, https://archive.org/details/mobot31753002212675

Kirtland, Jared P. “Report on the Zoology of Ohio.” Second Annual Report on the Geological Survey of the State of Ohio. 1838 pp. 157-200.

Download PDF:

Kirtland 1838 Geological Survey Ohio (3078 downloads )

Read: https://archive.org/details/annualreportong00mathgoog

Eugene R. Kuhne. A Guide to the Fishes of Tennessee and the Mid-South. Nashville, 1939, p36.

Read: https://books.google.com/books?id=EsMlAAAAMAAJ

Le Sueur, Charles Alexandre. “A new genus of Fishes, of the order Abdominales, proposed, under the name of Catostomus; and the characters of this genus, with those of its species, indicated.” In The Journal of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia. (Vol. 1, no. 1, May, 1817) pp. 88-96, (Vol. 1, No. 6, October, 1817) pp 102-111.

Download:

LeSueur New Genus Catostomus 1817 (3309 downloads )

Read: http://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/item/79416, https://archive.org/details/journalofacademy01acaduoft

Pratt, Henry Sherring. A Manual of Land and Fresh Water Vertebrate Animals of the United States. Philadelphia. 1935

Rafinesque, Constantine Samuel. Ichthyologia Ohiensis, or Natural History of the Fishes Inhabiting the River Ohio and Its Tributary Streams. Lexington, KY. 1820.

Download:

Rafinesque Ichthyologia Ohiensis 1820 Suckers (3393 downloads )

Read: http://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/ia/ichthyologiaohie00rafi, http://www.archive.org/details/ichthyologiaohie00rafi

“Suckerel.” The Century Dictionary. New York. 1900. (vol. 9, p. 6041).

Tomelleri, Joseph R., and Mark E. Eberle. Fishes of the Central United States. 2nd ed., 2011, University Press of Kansas.

Addendum

In my examination of hundreds of sources it became apparent that the vast majority of Cycleptus descriptions are condensed from—or outright copies of—two or three originals. What follows is one of the longer, more-detailed descriptions from the most active period (1880s to 1890s), bits of which, more or less word-for-word, appear in many other accounts of the species. (I have made no attempt to determine which parts originated in which sources or who copied from whom, and I don’t mean to imply that this is the source of the rest.)

“The black horse has an oblong, elongate, somewhat compressed body, very small head, long caudal peduncle and a forked tail. The greatest depth of the body is at the origin of the dorsal fin, and is one-fourth of the standard length; the length of the head is one-seventh length of body. The eye is small, being contained three times in its distance from tip of snout. Mouth small; the upper lip is thick and has several rows of tubercles, the lower lip not so thick and deeply incised behind. The pharyngeal bones are strong, with stout, wide-set teeth, which increase in size downward.

“The fins are large; the pectoral falcate; first three rays of dorsal high, the rest low; its base is considerably more than one-third length of body; anal very short. The scales are of moderate size, equal all over the body. D. 30; A. 8; V. 10. Scales, 9-02-9. Lateral line perfect, almost straight. The specimen described is No. 10,790, United States National Museum, from Ohio; length ten and one-half inches.

“This is known as the black horse, Missouri sucker, gourd-seed sucker and suckerel. It inhabits the Mississippi valley, is not uncommon in the Ohio river, and Prof. Cope records it as occasional in the Allegheny.

“The black horse reaches a length of two and one-half feet and a maximum weight of fifteen pounds. It is the best food fish of the sucker family. The sexes differ in color; the males have the upper parts jet black while the sides are black with coppery luster. The females are olivaceous with coppery shadings. The male has minute tubercles on the snout in the breeding season in spring. Dr. Kirtland noted a migration down stream at the approach of winter. The mouth of this sucker is small and the lips are covered with numerous tubercles.” 30

Footnotes

- Anything published before 1924 (as of Jan 1, 2019) is in the public domain in the U.S., as are government publications. Any image or copy of a work in the public domain—even if that image or copy was made or published later—cannot be copyrighted as it is not a new creation (though plenty of people and companies will try to claim copyright on such works). Each year on Jan. 1st another year of publications enters the public domain. In 2019, 1923 became public; in 2020, it’s 1924; 2021, 1925; etc. ↩

- Le Sueur, Charles Alexandre. “A new genus of Fishes, of the order Abdominales, proposed, under the name of Catostomus; and the characters of this genus, with those of its species, indicated.” In The Journal of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia. (Vol. 1, no. 1, May, 1817: pp. 88-96), (Vol. 1, No. 6, October, 1817: pp 102-111). Links in the bibliography, including a pdf download of everything in this source about suckers. More on LeSueur: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Charles_Alexandre_Lesueur. ↩

- Rafinesque, Constantine Samuel. Ichthyologia Ohiensis, or Natural History of the Fishes Inhabiting the River Ohio and Its Tributary Streams. Lexington, KY. 1820. Links in the bibliography, including a pdf download of everything in the book about suckers. More on Rafinesque: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Constantine_Samuel_Rafinesque. ↩

- Note: Current practice is to capitalize the common names of fish species. In the past this was basically random. For the sake of consistency, and to avoid the appearance of randomness, I have capitalized even unaccepted common names (except in quotations, which follow the original). ↩

- Agassiz, Louis. “Synopsis of the Ichthyological Fauna of the Pacific slope of North America, chiefly from the collections made by the U. S. Expl. Exped. under the command of Capt. C. Wilkes, with recent Additions and Comparisons with Eastern types.” The American Journal of Science and Arts. Vol. 19, no. 55. (May 1855) pp71-99. Links in the bibliography, including a pdf download of everything in this source about suckers. More on Agassiz: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Louis_Agassiz. ↩

- See http://txstate.fishesoftexas.org/cycleptus%20elongatus.htm for condensed information. Key sources for understanding the species in Cycleptus are: Hubbs, Edwards and Garrett 2008; Bessert 2006; Burr and Mayden 1999; Buth and Mayden 2001. (See this post’s bibliography for details.) ↩

- Kirtland, Jared P. “Descriptions of the Fishes of the Ohio River and Its Tributaries.” Boston Journal of Natural History. Vol. 5. no. 2 (1845), pp. 265-276, (and plates). Links in the bibliography, including a pdf download of everything in this source about suckers. ↩

- Jordan, David Starr. “Report on the Fishes of Ohio,” in: Report of the Geological Survey of Ohio, Vol. IV: Zoology and Botany, Part I: Zoology, Section IV. Columbus. 1882. pp. 735-1002. ↩

- Forbes, Stephen Alfred and Robert Earl Richardson. The Fishes of Illinois. Danville: Natural History Survey of Illinois, State Laboratory of Natural History, 1908. Links in the bibliography, including a pdf download of everything in this source about suckers. ↩

- Annual report of the Board of Regents of the Smithsonian Institution for the year 1883. Link in bibliography. ↩

- De Voe, Thomas F. The market assistant, containing a brief description of every article of human food sold in the public markets of the cities of New York, Boston, Philadelphia, and Brooklyn; including the various domestic and wild animals, poultry, game, fish, vegetables, fruits &c., &c. with many curious incidents and anecdotes. New York, 1867. ↩

- Goodholme’s Domestic Cyclopedia of Practical Information. New York. 1882. Link in bibliography. ↩

- Evermann, Barton Warren. “A Report upon Salmon Investigations in the Headwaters of the Columbia River, in the State of Idaho, in 1895, Together with Notes Upon the Fishes Observed in that State in 1894 and 1895.” In Bulletin of the U.S. Fish Commission. 1896. pp151-202. Link in bibliography. ↩

- Encyclopedia Americana, 1920. Link in bibliography. ↩

- See http://www.motherearthnews.com/real-food/growing-heirloom-gourdseed-corn-zmaz08onzgoe.aspx ↩

- Evermann and Cox (1896: 389) say of C. elongatus, for which they give the common names Gourd-seed Sucker, Missouri Sucker and Black Sucker, “This interesting sucker does not seem to have been taken often in the Missouri Basin, and how it came by the name ‘Missouri sucker’ is not apparent.” When they use “Black Sucker” (numerous times) in the report, it always means the species we now call White Sucker. (“A Report upon the Fishes of the Missouri River Basin,” 1896. Link in bibliography.) In the late 1800s, common names used for redhorses and blackhorses sometimes overlapped. An 1881 report from Ohio has Black Horse as a name for “Myxostoma macrolepidotum var. macrolepidota (Les.), Jor.” (i.e., Moxostoma macrolepidotum, Shorthead Redhorse), and uses Long Buffalo for Cycleptus. (Hobbs, Orlando. “A List of Ohio River Fishes Sold in the Markets.” In Bulletin of U.S. Bureau of Fisheries, Vol 1. Washington, 1881, pp. 125-26. Link in bibliography.) In 1930s Tennessee, the horses continue to have overlapping names: “The black sucker, Missouri sucker or black horse. This fish is the common black horse of the Tennessee river, though in both the Tennessee and Cumberland Rivers the black mullet (Moxostoma duquesnii) is also called black horse.” (Eugene R. Kuhne. A Guide to the Fishes of Tennessee and the Mid-South. Nashville, 1939, p36. Link in bibliography.) Name swapping is not limited to the distant past. A 1995 account of Ohio River fishing and culture says “blackhorse” is a local folk name for White Sucker and buffalo (though not which species of buffalo), and that the Blue Sucker is also called Black Sucker. (Lund, Jens. Flatheads and Spooneys: Fishing for a Living in the Ohio River Valley. University Press of Kentucky. 1995, p. 173.) ↩

- “Suckerel.” The Century Dictionary. New York. 1900. (vol. 9, p. 6041) ↩

- Cloutman, Donald G., and Larry L. Olmstead. “Vernacular Names of Freshwater Fishes of the Southeastern United States.” Fisheries, Vol. 8, No. 2: March-April, 1983. (It is sad that this article did not spawn a raft of similar efforts across the U.S.) ↩

- Coker, Robert E. “Keokuk Dam and the fisheries of the upper Mississippi River.” Bulletin of the U. S. Bureau of Fisheries. Vol. 45. 1929. pp87-139. Link in bibliography. ↩

- Coker, Robert E. “Studies of common fishes of the Mississippi River at Keokuk.” Bulletin of the U. S. Bureau of Fisheries. Vol. 45. 1929. pp. 141-225. Link in bibliography. ↩

- See prior note on this source. ↩

- See prior note on this source. ↩

- Jordan, David Starr and Barton Warren Evermann. A Check-list of the Fishes and Fish-like Vertebrates of North and Middle America. Washington. Government Printing Office. 1896. Links in the bibliography, including a pdf download of everything in this source about suckers. ↩

- Greene, Carroll Willard. The distribution of Wisconsin fishes. State of Wisconsin Conservation Commission. Madison, 1935. (Not in public domain.) ↩

- Pratt, Henry Sherring. A Manual of Land and Fresh Water Vertebrate Animals of the United States. Philadelphia. 1935. (Not in public domain.) ↩

- Coker, Robert E. “Water-Power Development In Relation To Fishes And Mussels Of The Mississippi” (Appendix VIII to the Report of the U. S. Commissioner of Fisheries for 1913.) Links in the bibliography. ↩

- Eddy, Samuel, and Thaddeus Surber. Northern Fishes: With Special Reference to the Upper Mississippi Valley. University of Minnesota Press. Minneapolis, 1943. And: Northern Fishes: With Special Reference to the Upper Mississippi Valley. University of Minnesota Press. Minneapolis, 1947. Links in the bibliography. ↩

- Eddy, Samuel, James Campbell Underhill and Thaddeus Surber. Northern Fishes: With Special Reference to the Upper Mississippi Valley. U of Minnesota Press, 1974. ↩

- “A List of Common and Scientific Names of the Better Known Fishes of the United States and Canada.” Transactions of the American Fisheries Society, vol. 75, no. 1. 1948, pp. 353-397. ↩

- Bean, Tarleton H. The Fishes of Pennsylvania, With descriptions of the Species and Notes on their Common Names, Distribution, Habits, Reproduction, Rate of Growth and Mode of Capture. In: The Report of the State Commissioners of Fisheries for the years 1889-1891. Harrisburg, 1891, pp. 24-25. Link and download in bibliography. ↩

Pingback: Blue Suckers for NANFA 2017 Convention in Missouri – moxostoma